Analytical Report on the Results of the Survey and Interviews of Volunteers

Volunteering is one of the most horizontal and resilient phenomena in Ukrainian society, especially during wartime. Volunteers rank third in the trust rating of the Ukrainian society (after the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the President of Ukraine), providing many socially important functions – from evacuating people from communities on the frontline to facilitating the education of children, integrating internally displaced persons, and more.

Given this, the goal was set to understand the specifics of how women volunteers perceive and undertake volunteer activities, their needs, and the characteristics of the relationships that arise between them.

To achieve this aim, a survey method through a Google form was used, involving 45 participants of the “Volunteer Women” project by YMCA, and semi-structured interviews (7 participants by targeted invitation).

Research Results

Volunteering

Survey participants have quite different understandings of what volunteering is: from the broadest understanding of volunteering as a certain ideology of citizenship to a narrower one, as unpaid work carried out on a voluntary basis. Common to the understanding of volunteering is the vision of its value during wartime for Ukrainian society. This value is primarily manifested in overcoming the effects of paternalism in the political culture of Ukrainian society, ensuring the resilience of Ukrainian society and the state, creating additional opportunities for self-realization, and building a system of common values for individual groups and society as a whole.

Distinct is the understanding of volunteering as a movement that emerged during the state of war. For a group of female volunteers, it is “Ukrainian samurai-ism,” working on challenges related to the war (assisting civilians, military, IDPs, animals, etc.), which can become somewhat of a professional job and occupy a significant part of working time. Meanwhile, another group of participants believes that volunteering should not turn into permanent employment, and as a result, cause harm to the person, their professional self-realization, mental, and psychological health.

Interestingly, participants who have been volunteering for more than 2 years approach volunteering more consciously: they rationalize the processes of volunteer work (understanding the goals of work, focusing on the goals and tools of work). On the other hand, participants who have actively engaged in volunteering in the last two years view volunteering more as an active civic stance, a mass movement.

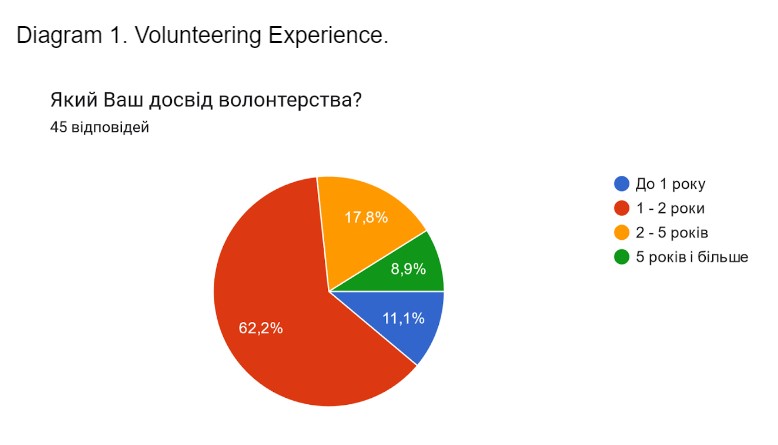

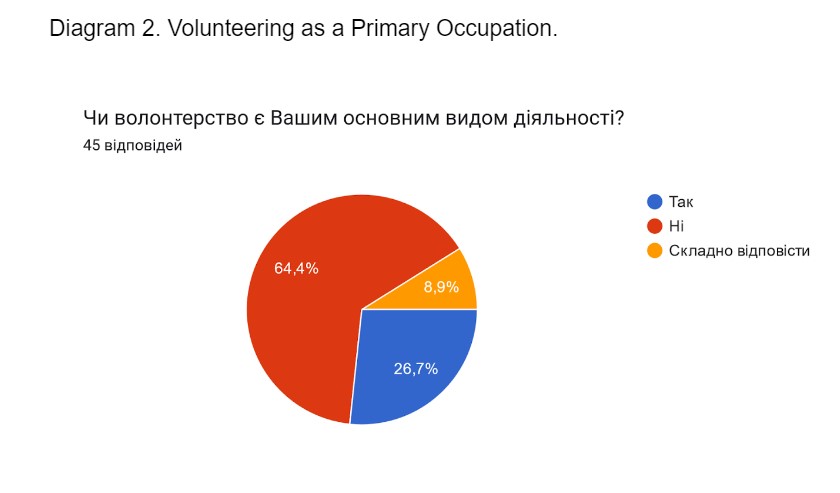

Diagram 1. Volunteering Experience. Yet, 26.7% of female volunteers dedicate all their time to volunteering, mainly activities related to the challenges of war. These volunteers face challenges in ensuring their own financial and material well-being, but prefer not to talk much about it. One considers herself a “husband’s dependent,” while another looks for ways to temporarily supplement her income (from respondents’ interviews).

Diagram 2. Volunteering as a Primary Occupation.

The survey revealed that the main thematic directions of the research are:

- Education and arts.

- Humanitarian aid to IDPs, vulnerable civilian population groups affected by war, people with disabilities, large families.

- Assistance to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

- Support for medical staff.

- Clearing ruins, construction.

- Animal aid.

In undertaking volunteer activities, female volunteers choose one of three trajectories:

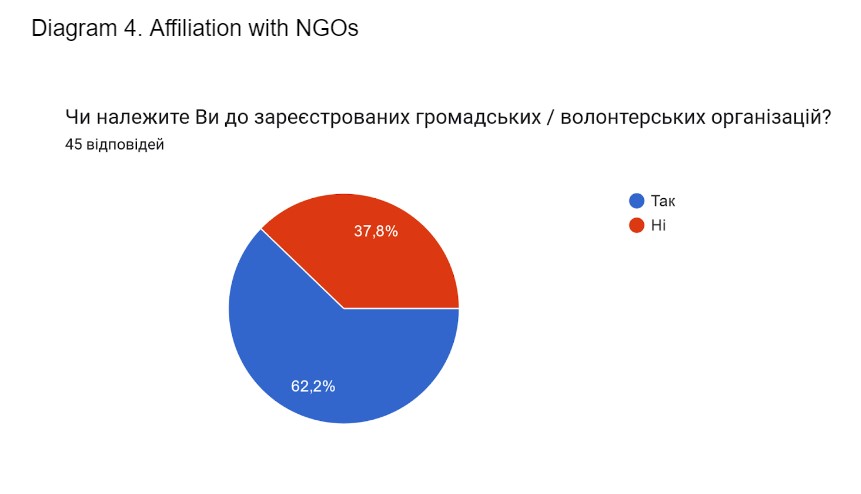

- Volunteering based on non-governmental organizations.

- Individual volunteering, without affiliation to NGOs or initiatives.

- Hybrid volunteering, joining volunteer networks and communities as needed.

The choice of trajectory depends on several factors, including:

- The importance of volunteering goals (the more important the goal – meeting the needs of the beneficiaries – the more likely the interaction with others).

- Trust (if there is a positive experience of cooperation, a vision of shared values).

- Working with the same group of beneficiaries (mainly, a local group, for example, the same front-line communities or military units).

A particular manifestation of trust is the concern for one’s own brand. Volunteers care about their own recognizability, their audience, and its care, which can suffer from cooperation with others.

The main arguments for working with non-governmental organizations are the safety of volunteers (feeling more protected, especially having an ID can make moving in front-line communities safer) and the ability to more rationally distribute duties and focus on one’s part of the overall mission.

Diagram 4. Affiliation with NGOs

Motivation and Ability to Volunteer

For many female volunteers, the most powerful motivation for volunteering is the feeling of the moment and the desire to help their country. “Doing everything you can,” “being useful,” helping – these are important responses about motivation. However, there is already a sense of fatigue – working until there is someone to work for, to the last.

At the same time, female volunteers are rethinking their own needs at this stage, with the main ones being their own financial stability, mental and psychological resilience, the need for self-realization, and safety. (see chart 5 “Needs of Female Volunteers”).

Chart 1. Needs of Female Volunteers

It is noted that there is a slight correlation between the definition of needs and capabilities by region. This suggests that the volunteers’ perceptions of their abilities differ in different regions, influenced by local factors, available resources, and the nature of volunteer activities in these regions. Those working in the Kyiv region consider themselves the least capable, while those in the Kherson region feel the most capable.

Also, there are distinct results in the assessment of one’s ability to attract resources depending on the experience of volunteering. The highest self-assessment of ability is among those who have been volunteering for 2 – 5 years, and for those who have volunteered less or more than this time, their self-assessment of ability is lower.

Volunteer Networks

Female volunteers have quite different understandings of what volunteer networks are, related to different understandings of volunteering as a phenomenon. The most common formulations are:

- Understanding the network as a circle of people “who are crazy, decisive, creative, and goal-oriented,” who may have different work tools, even different values, but the results of their work are cumulative and allow achieving important social goals – like Ukraine’s Victory, for example.

- A group of contacts: the ability to strengthen one’s and other volunteers’ capabilities. With this understanding, the expertise of network participants, their capability, and the possibility of cooperation are important.

- Events conducted for volunteers, providing an opportunity to better understand the overall picture of volunteering and surrounding events.

- A structure (organization, initiative) that takes on the functions of network administration, with a more formal approach (understanding who belongs to the network, what information and experience should be exchanged, what capabilities need to be strengthened, what challenges need to be overcome) (based on the Google form).

The fact that the understanding of the network is not yet actively used is confirmed by the answers to the following questions: “Do you belong to volunteer networks?” and “Which networks do you belong to?” Most participants answered the first question by saying they do not belong to any, but when answering the second question, they still indicated their affiliation with several networks.

Several important nodes of the network can be identified, among which are both individuals and organizations:

YMCA.Lviv”, “Peaceful Sky,” “Ordinary People,” “United to Win,” Ukrainian Football Association, “Student Brotherhood,” NGO “White Croatians,” UA Comix, “Wings of Hope,” Natalia Kruchinina, Boris Poshivak, Yuriy Vovkohon, Sergiy Prytula, Khristyna Konopatska.

The main motives for joining volunteer communities and networks are: the opportunity for information exchange, strengthening one’s ability to perform volunteer tasks, emotional support (“to understand” and “to joke” with one’s own – from interviews).

Over 50% of respondents believe that protecting the interests of volunteers is an important function of networks. However, less than half of the respondents see the network as a certain entity that can help regulate challenges, develop joint solutions (42.2%). See Table. Affiliation with volunteer communities:

Chart 2. Affiliation with Volunteer Communities

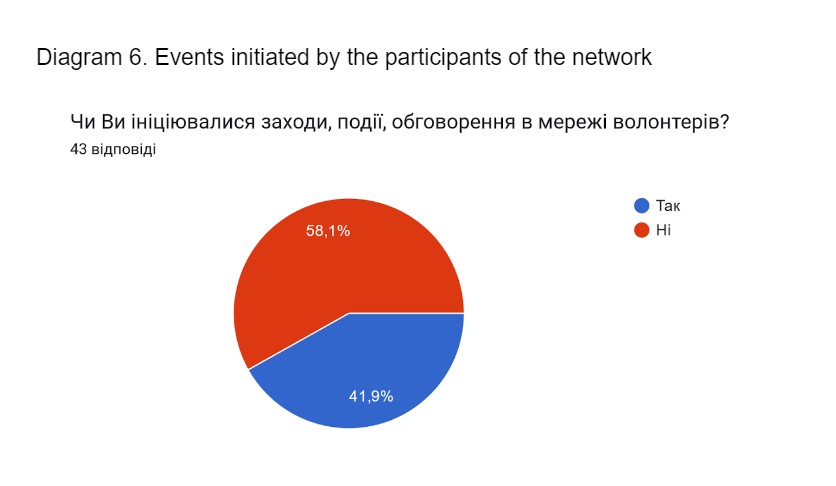

At the same time, not everyone is ready to share responsibility for the work of volunteer networks. Less than half have initiated events in volunteer networks. Many participants believe that responsibility lies with those who show initiative, and a third – with special organizations for network operations.

Diagram 5. Who organizes volunteer networks

Diagram 6. Events initiated by the participants of the network

Role and impact of YMCA

All respondents have experience cooperating with YMCA.Lviv, but the extent and rhythm of interactions vary significantly. It can be said that a certain core of volunteers (47.6%) has been formed, who interact with the organization on a regular basis several times a month. The other part of the volunteers interacts much less frequently.

In interviews, respondents define the role of YMCA quite differently: from someone who identifies active volunteers and enhances their capability, to the creator and main “owner” and administrator of the network. Respondents particularly note the opportunity for interaction with volunteers from different regions, the availability and possibility of using a safe space, and the concern for the mental health of female volunteers.

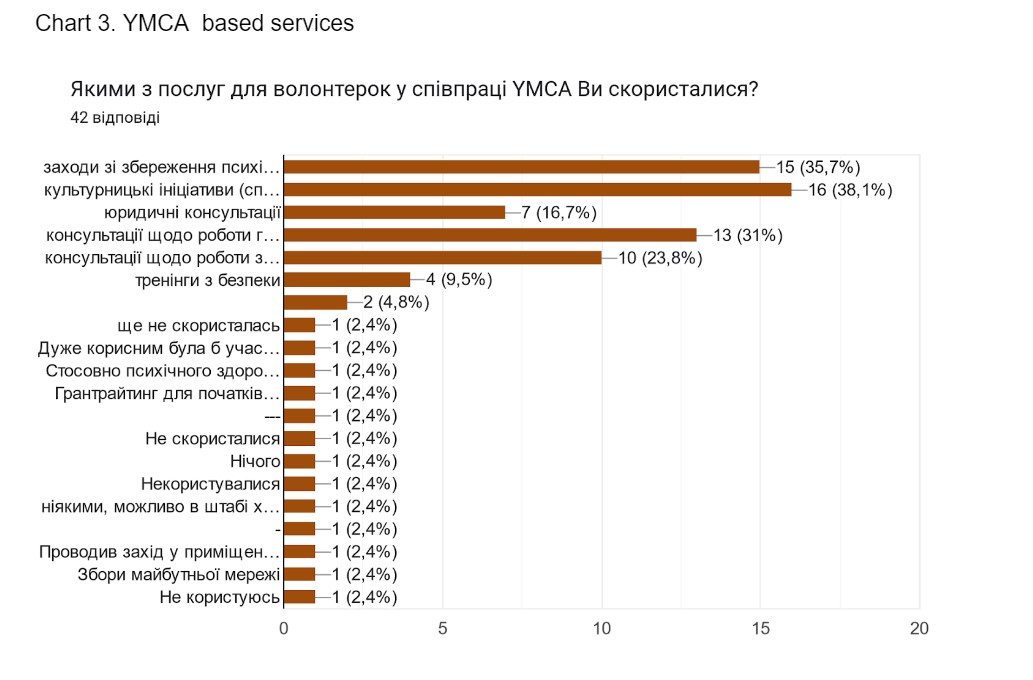

The volunteers primarily attend cultural and artistic events, master classes (which are part of combating burnout), use psychological support and consultations regarding work organization (see chart 3).

Chart 3. YMCA based services

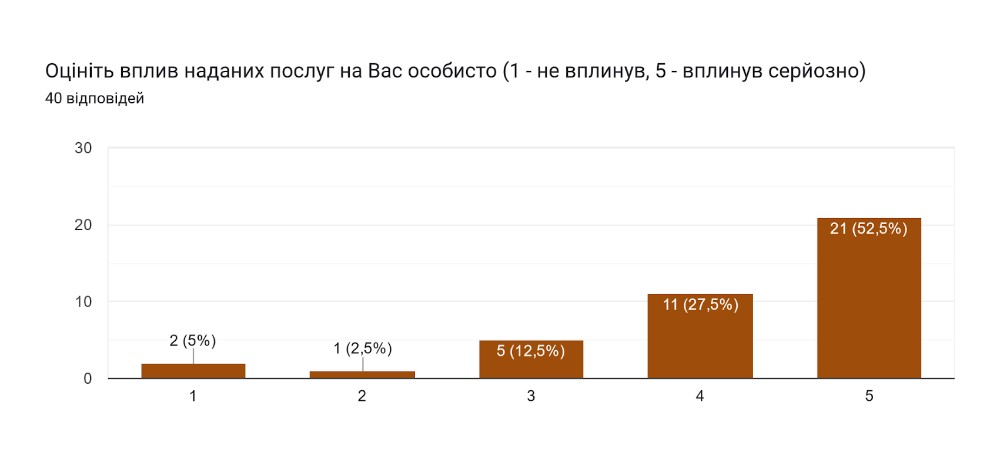

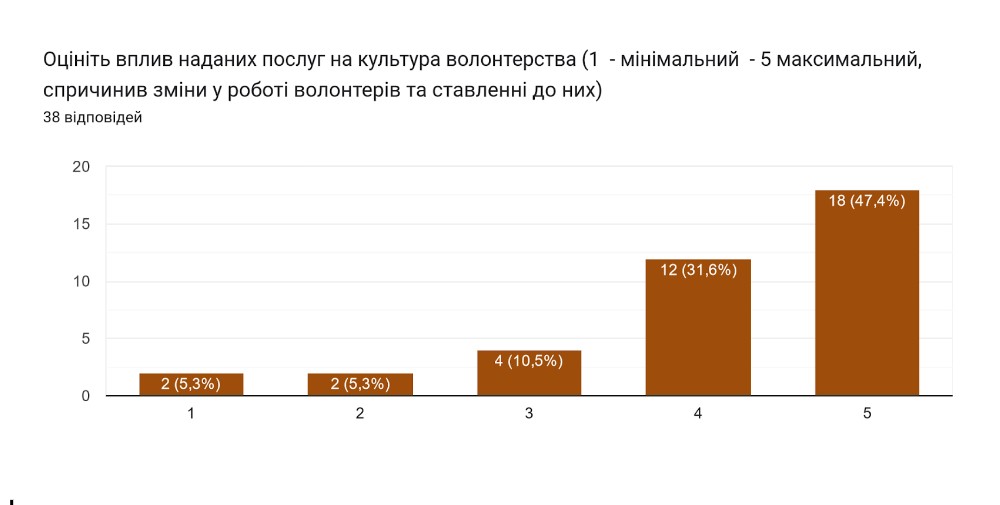

Participants of the project believe that the project has had an impact both on them personally and on the culture of volunteering as a whole (see charts below).

The impact on the culture of volunteering is defined through the rethinking of one’s own role in society. Volunteers believe that it is necessary to differentiate between volunteering and professional work, between paid and unpaid contributions to victory. The culture of volunteering also involves transparency and accountability in volunteer assistance, as well as the ability to communicate honestly with donors and to spread a culture of gratitude in our society.

Volunteers note that building and supporting volunteer networks is a complex process, and many of them lack the understanding and motivation as to whether it is worth investing in the development of networks. In particular, this is because there can be changes in the volunteer environment: connections are fragile, and there is a lack of systematic and stable projects. At the same time, networks are expected to prepare new volunteers and enhance the capability of existing ones. Among the biggest challenges is the exhaustion of volunteer communities: “we are running out.” Volunteers also express concerns about stable relations with the state: “the state may encroach,” change the rules of the game, which can complicate the work of volunteers. However, volunteers have little resources and ability to form a unified voice for dialogue with the state.

Conclusions

- Volunteering is becoming more rationalized. This means that there is a need for more exchange of experience regarding the systematic organization of volunteers’ work. Such exchanges can contribute to more effective work and strengthen the impact of the entire volunteer movement.

- Overall, volunteers positively assess their ability to work with donors and target groups. However, the most concerns arise with paperwork and reporting. The strongest motivation is among girls with 2-5 years of volunteer experience. It is important to support the group that is on the verge of 5 years of experience.

- The main challenges at this stage are working with the financial stability of the volunteers themselves (especially those who dedicate more than 50% of their time to help), as well as the problem of self-realization of volunteers. It is important to create conditions for them to realize their potential during and after the war.

- Networks are an important element in the activities of volunteers. For them, it is primarily an opportunity to exchange information and a safe space where they can be among their own and recover. However, volunteers are not ready to actively engage in supporting networks; they need institutional organizations with the necessary experience and resources for this.

YMCA. Lviv is one of such organizations that can ensure the sustainability of volunteers’ work, mental recovery through art therapy and work with psychologists, and provide a safe space that empowers volunteers to continue their mission.