Ten years of the marathon, a race that is the length of our youth and distorted happiness, a marathon that has bitten into our destiny and taken away the safety of our children, many of whom were born during the war, who play, grow, learn, fall in love in times of war… And we only wish that they would grow up more slowly and not wear armor when they become adults.

I would like to know the deadline of this marathon, the finish line – the day or week when all projects and operations are completed and you exhale. It’s the same for me with books: you write non-stop, you don’t sleep, you don’t always eat, give it your all, but you have a deadline. Sometimes it gets late, the editor “turns a blind eye” and I turn it in two weeks later. And I love these deadlines, they give me a kind of guarantee of confidence and a small, super-local, but undoubted victory. If it was possible to do this with war… I have talked to soldiers about this and they unanimously say that they would charge with all their might and plow for two, three, five or even ten years, but knowing the deadline, even if it is a mistake of two or three weeks.

But there is no deadline, and there will not be one. I’m not sure if it was only my husband who had to fight, or if my son will have to do it as well… He’s not 16, he’s 6… But sometimes I’m even afraid of this victory. Because every day it takes someone away, giving hope that it is “in the name of victory” and saying loudly: “Heroes do not die.” They do! And I don’t know how many more the war will take. And after it, those who are not included in the list of those who died in the name of victory, with their name and unit, will face a painful return.

It’s different for everyone. Those who fought honestly will be silent, just as the cyborgs of DAP or the steel men of Azovstal were mostly silent. They won’t wear uniforms, they won’t wear victory chevrons, they will try to get on with their lives. To try at least, because if they go to war as twenty-five-year-olds, they risk returning from it in their forties or fifties. And they will have so little time to live….

Victory is not only about the reclaimed and liberated territories, definitely not about the message broadcasted live – “Victory. Russia surrenders.”, it is not about the blue-yellow flag over moscow; victory is about our minds. Someone will read about the victory in Telegram and be happy – a trip to the seaside, a new car. And for someone else it’ll mean time to erase from his memory the unimaginable horror they lived in before…

It’ll mean your friend’s severed leg; a direct hit from a tank on your comrade’s head; that one time you applied a tourniquet on yourself and couldn’t twist it properly because you didn’t have the strength; the child dying before your eyes in Bakhmut; the unfinished cigarette that made you quit smoking altogether; the still-warm leg of a dead officer, which you held and hid behind; the grandmother, whom you tried to take out of the combat zone, but she was hit by a mine in front of you; digging up a friend whose leg was still twitching and you pulled out your nails and scattered the earth to take him out; the cherry you saw every day from the trench but couldn’t taste because it had someone’s insides hanging from it; the abandoned wounded you couldn’t bear to carry; the encirclement and the commander’s message to “take up a circular defense” or even your first battle; not being able to go to the toilet because the shooting didn’t stop all day; captivity, when you had nothing better to do than to bully the russian paratroopers in a ratio of one to ten; the electric shocks in the occupiers’ prisons as a daily “ritual”; the moaning in the neighboring cells; the raped girl who had to have an abortion because she would hate a child from a russian soldier; the wounded enemy whom you wanted to kill but could not.

There will be anger and resentment – against the occupiers, against those who fled through the Transcarpathian forests, against the civilians who wanted a stronger counteroffensive, against all those who were “not born for war”, against the rear guard who mobilized you and stayed to guard the military commissariat, against the commander who burned the volunteer’s car, against the dog who went crazy after the concussion and bit you, against the local who put poison in the jar of compote. A lot of resentment, pain, and anger. With this baggage of emotions, it will not be easy to get on a plane and fly to Egypt after the announcement of victory. But despite this baggage, you will remember the flags on the road to liberation and the people who dug up their flags, hidden in their yards, and went on to pick flowers from the garden to throw them at our cars in gratitude. You’ll remember the local hunters with rifles who shot at the enemy vehicles, you’ll remember the delicious pies of a grandmother from Kherson region, the hot borscht of a woman from Izyum, and the local hairdresser giving away the enemy positions. And then you will want to live, and the pace will be faster, and you will want to live more and be in time…

The main thing is to be in time.

That’s why I want to win so badly, so that those who survive will be allowed to live…

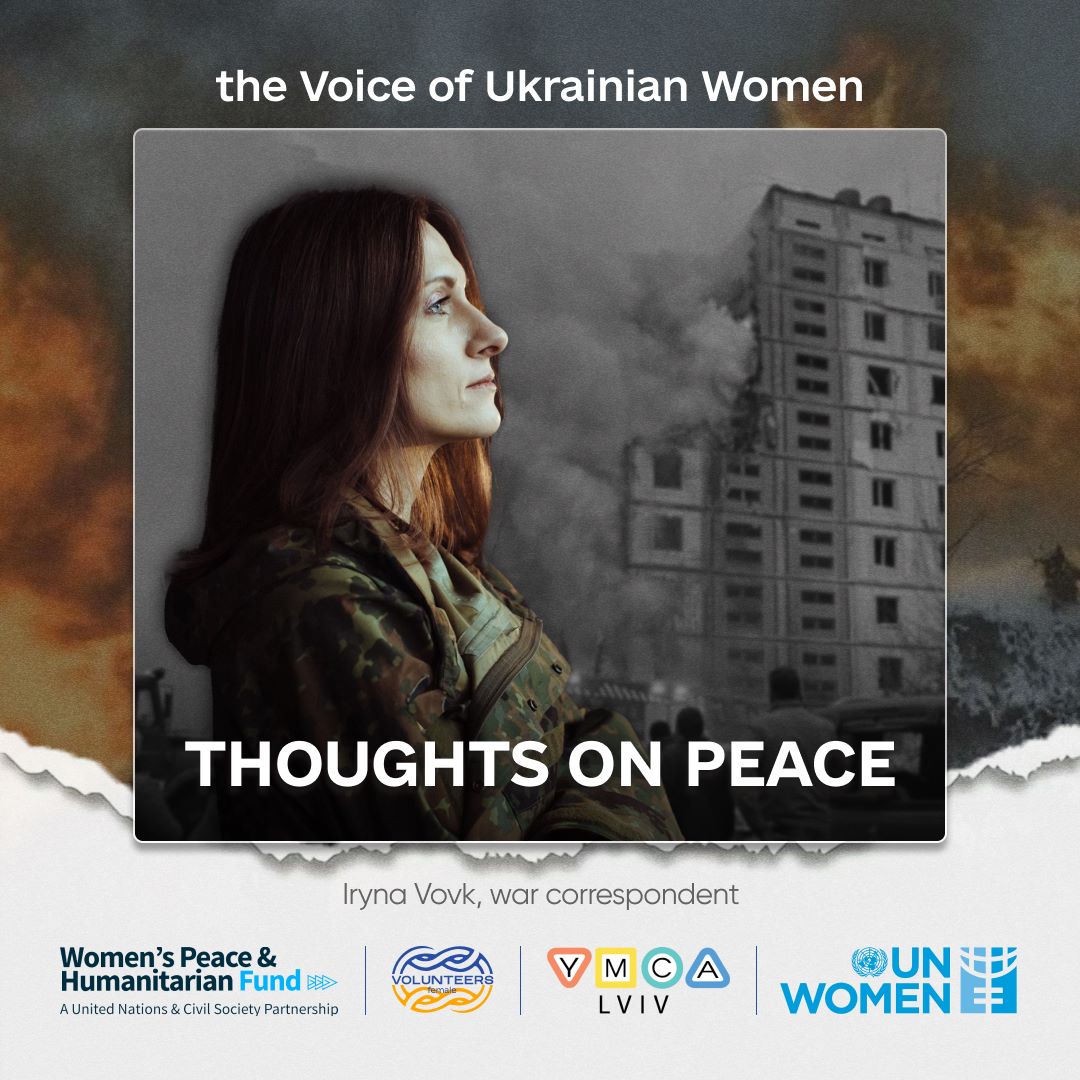

Iryna Vovk, war correspondent

The initiative is implemented within the framework of the project “Strengthening the capacity of the women’s network of volunteers in Lviv region” (#FemaleVolunteersLviv) with the technical support of UN Women Ukraine and funded by the UN Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF).

The WPHF is a flexible and rapid funding instrument that supports quality interventions that increase the capacity of local women to prevent conflict, respond to crises and emergencies, and seize key peacebuilding opportunities.

* This publication has been prepared with the financial support of the United Nations Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF), but the views and contents expressed herein are not necessarily those of the United Nations and are not officially endorsed or recognized by the United Nations.